The name of Billie Holiday brings to mind a distinct era and mood, both a moment frozen in the cultural annals of time and eternal, encompassing all of America’s musical heart.

Her voice is that of legend, not to mention her looks, her songs, her style, the way she lived. The artistry of Billie Holiday was forged in humble beginnings, meager circumstances, and blossomed in the first hothouses of jazz improvisation and blues imagination during the eras known for swing, big band, and bebop. As we celebrate what would have been Lady Day’s 110th birthday, we acknowledge the very audacity of such a creative soul to distinguish herself through her singular vocal artistry, her songwriting skills, and her commitment to social justice.

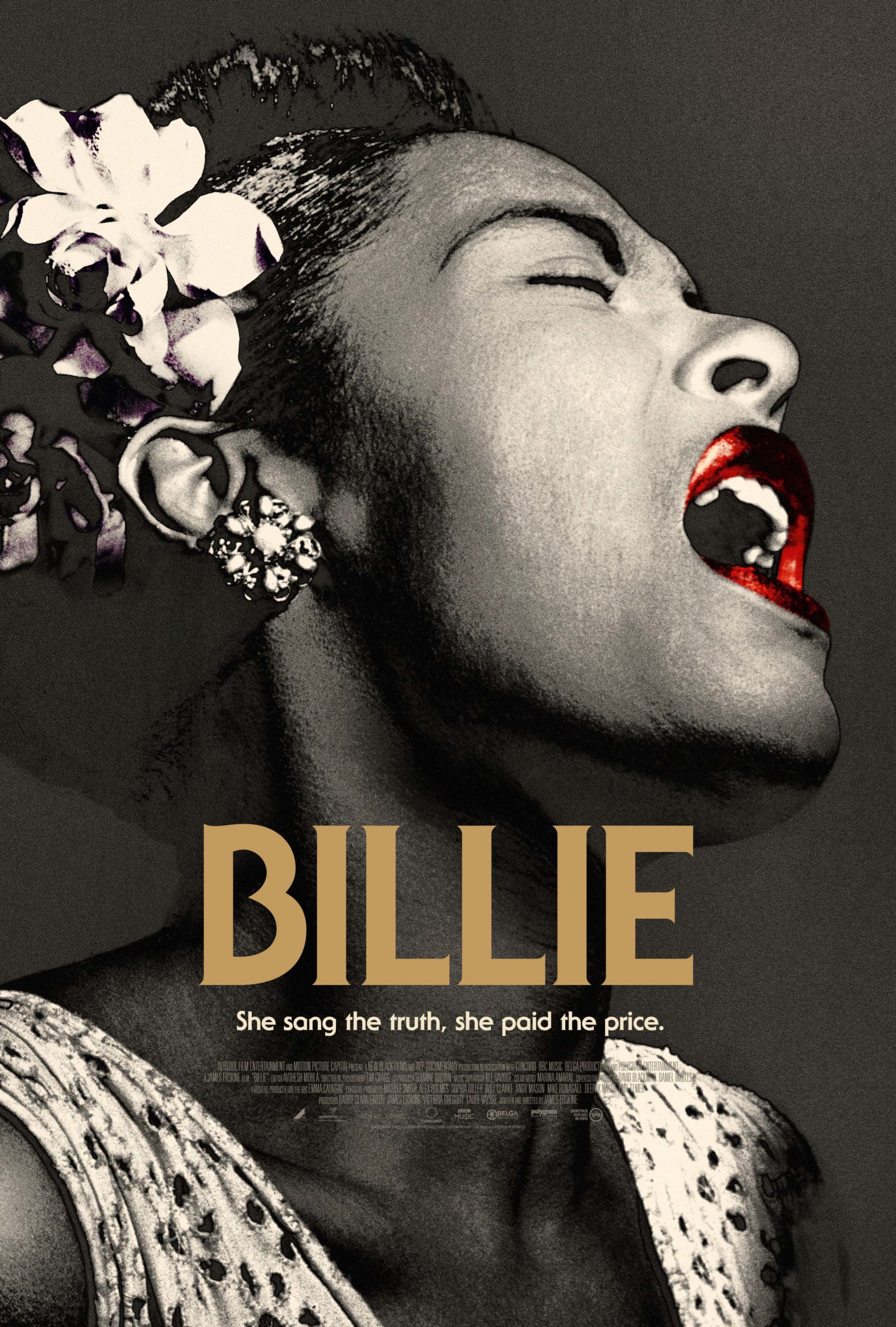

Her legacy is so powerful that her life has been immortalized in film, most notably in 1972’s Lady Sings the Blues, the adaptation of Billie’s 1956 autobiography, which starred Diana Ross. Billie’s story was captured again in the 2019 documentary BILLIE, using never-before-heard interviews with people who knew Holiday, from childhood friends, to band members, to F.B.I. agents. More recently, singer Andra Day portrayed Holiday in the 2021 film The United States vs. Billie Holiday, which focused on Holiday’s struggles with racism and the legalities of performing her indelible anti-lynching anthem “Strange Fruit.”

Her commitment to transforming the poem “Strange Fruit” into a powerful cry against America’s racial injustices is just one aspect of the treasures she left behind. Her renderings of “I Cried for You” (her first big hit), as well as her compositions “God Bless the Child” and “Lady Sings the Blues,” have cemented her place in American music history.

A Legacy of Audacity

Many have since tried to emulate her intimate yet quirky timbre, her plaintive blues moan, her last-one-out-the-door phrasing. But there was only one. Perhaps to her, being so unique was both a blessing and a curse. How dare she be different yet true to herself? How dare she be strange but also familiar and relatable? How dare she give the smoothest ballads of the day a poignant sense of regret, and render the roughest blues complaints the lightest strains of hope for better times? If she did not dare to be herself, we would not have so much to celebrate.

Billie developed the nerve to be who she wanted and do what she wanted early on. Life was not a gold-paved pathway for a girl child of color, during the days of Jim Crow and segregation, to teenaged parents living on a wing and a prayer. Billie arrived as born Eleanora Fagan in April, 1915 in the town of Philadelphia, then an enclave for Blacks who had taken part in the Great Migration north from the strictures of racist living in the South. She spent her first years in Baltimore.

Forged by Fire

At age 12, Billie — young and rambunctious, wild and fearless — worked beside her mother in one of the few professions where Black women could find steady work, as a cleaning woman and errand girl. That they worked in a house of ill repute no doubt provided many life lessons for young Billie. Some were lessons she probably wished she never had to learn. These experiences gave young Billie a veneer of toughness — a quality anyone needed to survive in those rough and tumble days of bathtub gin, Harlem Renaissance writings, dance hall frenzies, jazz club sessions, and the whiplash years of the Great Depression to follow. Young Billie had long admired the recordings of blues legend Bessie Smith and New Orleans jazz master Louis Armstrong, learning her timing, pitch, and improvisational skills by singing along. Billie took all the tumult and the trials of her youth, storing them up inside, letting them inform who she was and infusing them into the artist she would become.

With her mother, she moved to Harlem in 1928, a time of Roaring Twenties licentiousness where Harlem was an entertainment capital for anyone who could afford it. Determined to do what she could to get by, Billie began showing up at Harlem’s many jazz clubs, auditioning for a spot at the microphone and sometimes just singing for tips. As her reputation grew after performances at a string of popular New York nightspots, Billie was seen singing at Covan’s in Harlem by legendary producer John Hammond. He invited her into the studio to make her first recordings. She was just 18.

In the age of jukeboxes and victrolas, recordings were what helped garner attention, notoriety, record sales, and more singing engagements for a performer. Billie Holiday’s one-of-a-kind sound made her more sought-after than ever. She recorded and performed with some of the most popular bandleaders of the times: Benny Goodman, Teddy Wilson, Count Basie, Artie Shaw, and others. On early recordings she was often accompanied by her friend, the saxophonist Lester Young, who was the first to dub her “Lady Day.”

She performed across the country with Count Basie’s Big Band from 1937 to 1938 and then began a stint as the vocalist with Artie Shaw, making her the first African American woman to sing with a white orchestra — a fact that often caused them trouble on gigs booked through the segregated South. One can only imagine the nerves of steel, the fortitude, the audacity it took for Holiday to face the tide of racial abuse from audiences, even for the short time she toured with Shaw’s band.

Gardenias and Glamour

It was during the era of the big band “girl singer” that Holiday cemented not just her vocal style, but her physical presentation. Women who took the stage backed by a full orchestra were expected to represent a certain air of glamour and sophistication. Billie did this not only through her choice of stage gowns, but specifically through her image: mostly upswept hair, a simple but distinctive red lip, and the ever-present gardenias in her hair.

Flowers being worn regularly by women for more than proms, birthdays, and weddings was common in those times. Corsages pinned to collars and waistlines, worn on wrists, and in the hair were part of a well-dressed woman’s fashion arsenal for a day or evening out. Even Billie sang a version of “Violets for Your Furs” on her last full recording, 1959’s Lady in Satin.

Billie was not the first or only female jazz artist to wear flowers in her hair. Yet, she made the look a distinctive signature. Creamy in color and texture, tropical in origin and possessing a captivating scent, gardenia blooms seemed the perfect accessory. Positioned in her hair, against the singer’s angular face seemed to create a balance of softness against the sometimes grittiness of her vocal stylings, as well as a reminder of earthy beauty for an artist whose private life was sometimes less than smooth. This signature look ensured that Billie would be remembered not only for how her creativity impacted our ears, but how she delighted our eyes as well.

Vocals Unlike Any Others

The sound of Billie Holiday is not easily forgotten. Starting her recording career in the 1930s, she began in an era where unique voices were seen as novelties. Many recordings of the ’30s were made to immortalize stars of the Broadway stage and the silver screen. Billie’s popularity endured, though her vocal stylings went against the grain of what became the norm throughout the 1940s and 1950s: elegant song stylists, smooth crooners, hepcat improvisers, and sassy chanteuses. Billie’s poise, timing, phrasing, and interpretation skills were so unique and fascinating as to make her undeniable as a creative genius, but almost inimitable as well.

Think of her performing contemporaries: the smooth sophistication of Sarah Vaughan; the bell-like timbre and scat playfulness of Ella Fitzgerald; the cool and sassy demeanor of Lena Horne. White movie icons like Judy Garland, Doris Day, and Rosemary Clooney had their own middle-of-the-road Americana approaches, and smooth crooners like Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, and Bing Crosby lulled listeners with their satin sounds. Billie took many of the same songs performed by these artists and made them unmistakably her own. Some might have said that Billie’s measured, mannered approach to a song was a gimmick, but it was so true to her sensibilities that her music inescapably touched and transformed listeners. She sang with a true jazz performer’s ear, her voice close in sound and execution to the brass and wind instruments that accompanied her on stage and in the studio.

In celebrating Billie Holiday’s 110th birthday, we remember a singular artist who stood up to the hurdles placed before her, showing the grit that helped define her style. For the brief span of time she spent in the spotlight, her candle burned brightly enough for us to see more than six decades after she left us.

By Janine Coveney

March 2025

Billie Holiday NEWS ARCHIVE

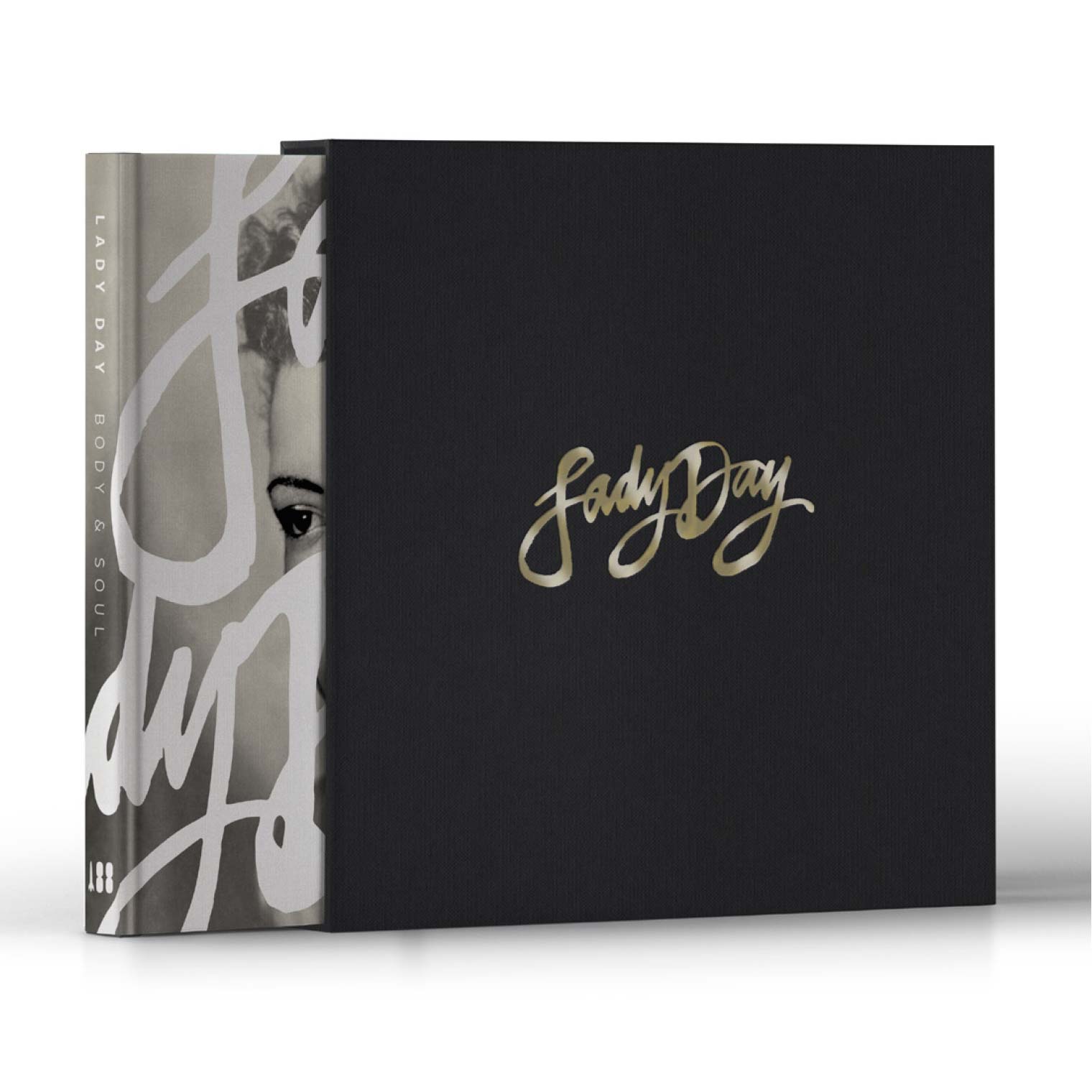

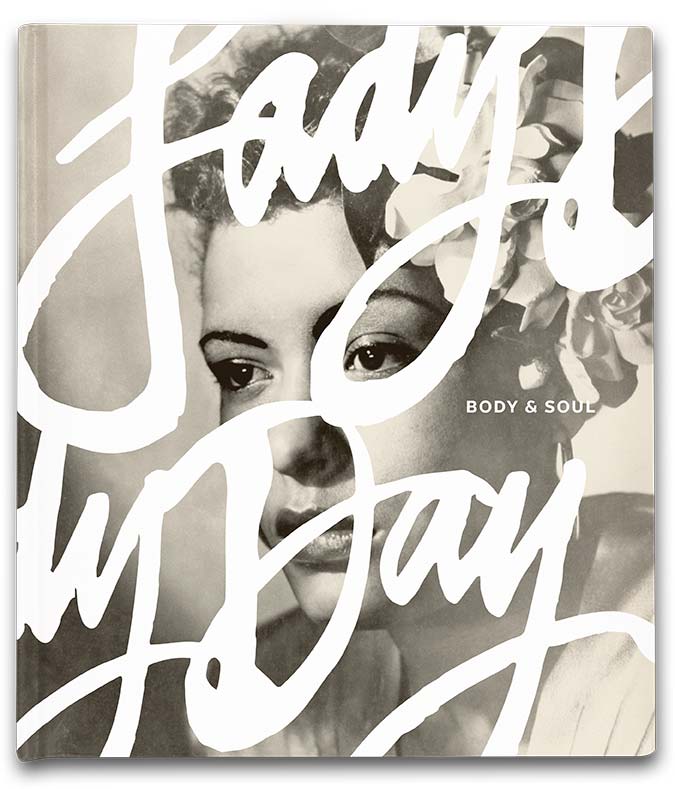

LADY DAY: BODY & SOUL – OFFICIAL BILLIE HOLIDAY BOOK – PRE-ORDER NOW

Announcing the first official illustrated book tribute to Billie Holiday

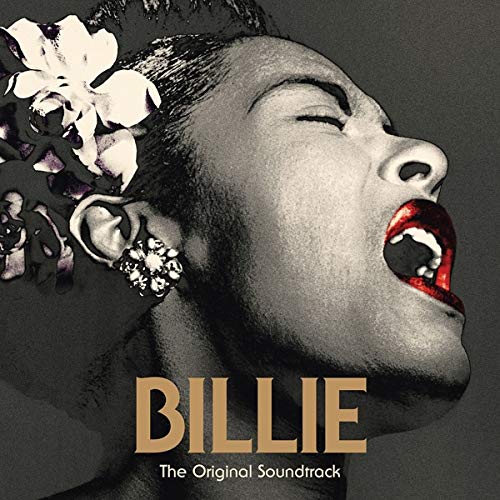

OFFICIAL COMPANION SOUNDTRACK TO UPCOMING DOCUMENTARY “BILLIE” TO BE RELEASED NOVEMBER 13